I had a great time at my first AWP conference last month—so happy I met some of you in person, as brief as it was! I also loved participating in the Must Love Memoir Reading Series earlier this month—some highlights below, and you can find more on my Instagram. I hope you’re all doing ok and finding love and community in these times of fascist cruelty…

vesna

Books

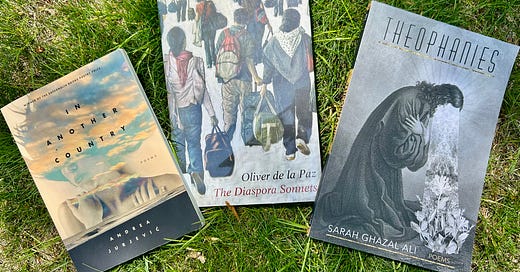

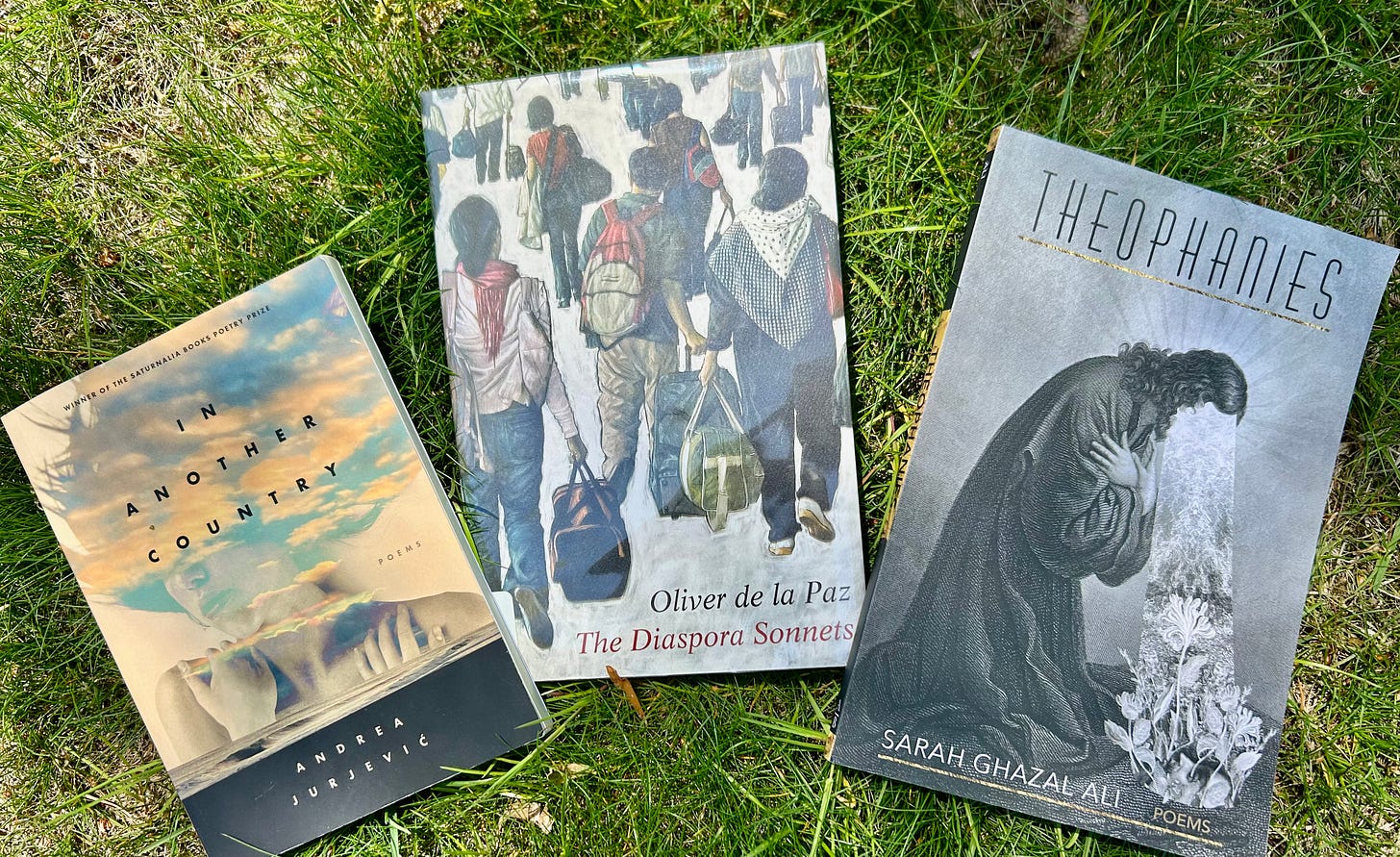

I almost always feature memoirs in this section, but since April is National Poetry Month and I’m trying to read more poems, I decided to focus on three beautiful poetry collections: In Another Country by Andrea Jurjević, a fellow Croat whom I got to briefly meet at AWP; The Diaspora Sonnets by Oliver de la Paz, whose books several writers have recommended to me; and Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali, who I met during my Hedgebrook residency.

I unfortunately have no poetry training, so I can’t come up with clever criticisms and comments about why I picked these three, but I can tell you they all moved me in different ways. I deeply related to Andrea Jurjević’s writing on everything from fish to language to our broken country of Yugoslavia. I love how she approaches topics such as war and longing, and felt so much of my childhood and nostalgia in this gorgeous book.

Oliver de la Paz writes beautifully about his family leaving the Philippines, their challenges trying to create a new home in the United States, and what it means to live in the diaspora. Whether situated at a laundromat, on an interstate, or at a baggage carousel, his poems evoke the tenderness and displacement often embodied in migration.

And in Theophanies, Sarah Ghazal Ali uses precise and visceral language to explore subjects like women’s bodies, faith, and family. The Pakistani-American writer plays with form to craft these poems, which take us on an empowering journey across cultures, gender, and womanhood.

Essays and Interviews

I’m a big fan of airport stories—my family used to spend so much time doing pick-ups and drop-offs at Toronto’s airport that our hairdresser was based at one of the terminals. Here is an essay set in an airport that is about traveling, what makes a place home, and more. For off assignment, Rebecca Emiru writes To the Girl at the Airport in Addis.

“I’ve moved back and left Addis again several times since then, but that initial move was a turning point. In Addis, I grew up in a thick web of meaning. Everywhere I looked, I had aunts, uncles, cousins, friends. Even if a lot of people eventually left, the fact that they had been there before made Addis feel like the heart of our collective.”

I look forward to reading Sarah Aziza’s The Hollow Half, out this month. Here is an excerpt in Electric Literature, In Palestine, Searching for the Remains of My Grandmother’s Village.

“This job was the first time since my own childhood that I moved fully in Arabic. While I had returned to the language years before, this had come in the form of classes or sporadic conversations. Those Nablus mornings, there was no classroom formality, no sense of scrutiny. Any stumbles in grammar or conjugation dissolved into the bright chaos, and the children’s replies did not miss a beat. Khaltu! they called to me. Auntie, look! They waved fingerpainted pages, glitter on their elbows, in their hair. My Arabic tongue loosened, my throat filling with remembered, or inherited, words. I smiled for hours straight.”

I have featured Marcello Hernandez Castillo’s work in this newsletter before; he is among the curators of a beautiful anthology, Here to Stay: Poetry and Prose from the Undocumented Diaspora. Here is a quote from one of the poets, féi hernandez, from this wide-ranging discussion in The Rumpus, “A Here that is Not This”: An Undocupoets Roundtable Conversation.

“My new book coming out is titled (Un)Docu Mente. I’m a naturalized citizen, but going back to these fictions, even in other poems I’ve written, the question is, “Mom, are we actually safe now with this green card? Mom, are we actually safe now with this naturalized citizenship?” Because it is fiction. There’ll be a moment when you know what? Any naturalized citizen from the last ten years is also going to get deported because . . . fiction . . . because we said so. These questions have always been at the root of my work: What is reality? What is fiction? How are they collapsing on each other?”

I had the pleasure of taking a workshop with Rajiv Mohabir at Kenyon last year and it’s always wonderful to come across his byline. I appreciated his comments about the elasticity of language and who gets to translate in this interview for Words Without Borders, “Swimming in an Ocean the Same Temperature as Your Blood”:A Conversation with Rajiv Mohabir.

“I think of mythology as a framework for understanding our contemporary realities—that we code ourselves in metaphor. My poetry and writing are shaped by the nuances and shades of the Guyanese Bhojpuri my Aji called Hindustani. It’s poetry: the cane fields, the scorpions, the marriages, the deaths, the lashes, the subjugation, the patriarchy, the survival, the settler colonization that we inherited—all of this lives inside of me as I continue to move and dance across this North American continent.”

Here is a heart-wrenching piece about the Los Angeles fires for The Rumpus, Home is a Word Unspoken by Tamar Mekredijian.

“My husband, our parents, our aunts and uncles—they are immigrants displaced by war. After our ancestors were exiled during the Armenian Genocide, many settled in Beirut, Lebanon. Later, war and civil unrest forced them to flee to the United States. They knew what it was like to be pushed out of their homes. To hide in dark stairwells with their neighbors. They came to America because they believed they were not only saving themselves, but their future children and their children’s children. All my life I listened to their stories of the horrors of war, of hunger, of not knowing where they would sleep that night. I saw the effects of violence in their lives. The secrets they kept. The mistakes they made. They way they recovered because survival was the goal. It was the only option. Pushing through the pain was their only way forward, for the sake of all of us.”

For LitHub, here is another excerpt, “The Past is Another Country.” On Fate, Grief and the Slow Disintegration of a Family in Zimbabwe, by Peter Godwin.

“The arrows unleashed at my mother during her half-century in Southern Africa have been many and sharp. She was overtaken by Zimbabwe’s civil war, in which her only son and her husband fought, and which claimed the life of her elder daughter, my sister Jain, at the age of twenty-seven, and Jain’s fiancé, when they drove into a Rhodesian army ambush three weeks before their wedding. My mother served as a doctor in Zimbabwe’s biggest hospital while HIV ravaged the population, before there was any effective treatment.”

Diana Ruzova writes about the role of cousins in immigrant families in First Friends, Once Removed for The Conversationalist.

“As new immigrants from the former Soviet Union, my parents relied on the built-in community of care provided by our extended family: an old-world-style network of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. But while the adults in my family did play a role in my Los Angeles upbringing, it was my cousins who did the majority of the caretaking.”

Here is a familiar name for readers of this newsletter—Viet Thanh Nguyen on Finding the Foreign in Ourselves and Those Most Like Us, in an excerpt from his latest book, To Save and to Destroy: Writing as an Other for LitHub.

“In the end, we cannot escape from otherness, because otherness exists within us and our humanity. Fernando Pessoa, who was born and died in Lisbon, wrote that “To live is to be other,” foreshadowing Derrida’s concept of otherness as being elusive, and evoking, perhaps, the idea that otherness is more important as a principle and an orientation, rather than an identity, which can be self-serving. Can we therefore find a degree of joy in our inevitable otherness, versus trying to do the impossible and dispel our otherness and our others, especially when doing so often involves shame and violence?”

I’ll end with this New York Times interview—Isabel Allende Understands How Fear Changes a Society.

“It would be very hard for me to write a novel about a submissive wife in the suburbs that waits for her husband to come back from the job. There’s no story there. I write about women who are always challenging convention and get a lot of aggression for that, but they stand up, and they are able to fend for themselves. Those are the characters I love, and I write about them because I know them so well. I was born in a Catholic, conservative, authoritarian, patriarchal family in the ’40s. Women of my generation and my social class were supposed to marry and have kids, and that’s it. So to get out of that prison of the mind was very challenging. I belong to the first generation of women who were able, some of us, to do it.”

Thanks for reading,

Vesna

About this newsletter: Writing about immigrant and refugee life—the struggles, triumphs, and quirks—by immigrants and refugees, children of immigrants and refugees, and others living between countries and cultures. For more info, here is a Q&A I did with Longreads about the newsletter. Photo in the logo: Miguel Bruna/Unsplash.

About me: I grew up in the former Yugoslavia, then immigrated to Canada, and now live in the United States, where I work as a writer and communications consultant for nonprofits in the human rights and international affairs fields. I have written for Back Where I Came From: On Culture, Identity, and Home, Connecticut Literary Anthology 2024, Connecticut Literary Anthology 2023, The New York Times, Pigeon Pages, the Washington Post, the New York Daily News, and Catapult, among others. I was a Writer in Residence at Hedgebrook (‘25), participated in Tin House (‘24 and ‘21) and Kenyon Review (‘24) workshops, and won the Poet & Author (‘24) and Parent Writer (‘20) fellowships from Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing. Find me on Instagram and Bluesky.

Beautiful piece. It was such a nice surprise to meet you in LA, Vesna!

Thanks for writing. the newsletter I keep aside for when I've got time, peace and quiet 💜